Need to read

like breathing

Like many others, I am an Australian by choice but, partly still, African in sensibility. It is likely, therefore, that I would slip into narrative almost without thinking.

It is equally likely that if a story is beautiful or intriguing I would be captured, a willing walker on whatever journey the story is unfolding.

Which is not to say that people are more avid readers in South Africa, the part of Africa in which I spent my childhood and early adulthood. Indeed they are not. “She’s always got her nose in a book,” aunts would say of me as though that were a little odd. “Go out there and be sociable,” my Dad would say when he would discover me, mid-visit to friends or relatives, in thrall to a whole bookshelf of someone else’s books. “Get some fresh air,” my mother would say, shooing me out of the house.

But there is, in Africa, the unspoken acceptance that a story is a legitimate excuse to stop whatever you are doing for a little while, the certain knowledge that a story is not just a story.

You listen to a story with your ears, but you absorb it with your whole body. If every bit of you is paying attention, you are being soothed or excited by the rhythm of the storyteller’s voice, cajoled by the words offered, enticed by the call to your curiosity. Your heart might quicken, your diaphragm contract, your toes curl or the hair on the back of your neck might rise as the words find their mark.

In a story you never know when you are going to be struck by truth or whether that truth will be some small thing or a shift of your psyche. So you offer yourself to the story in the hope that you will learn something so truthful that it will make everything clear.

In the story of how I came to love books, oh, let’s not be coy about this… in the story of how books came to be my passion, how it came to be that life itself became enmeshed with books, there are many meanderings, little paths that seem at first to be distractions, but these are pleasant interludes and often lead back to the original path, just in a different place, where the view is a little altered.

Imagine a child growing without television, amidst the lush green of the sub-tropics. The sun shines, frangipani and flamboyants bloom. In the long grass pythons and deadly mambas shiver the masking stalks.

At the edge of domesticity there is always danger. Silly ducks, walking in a daily line to the pond, are eaten, one by one, by a leguaan, its reptilian stealth and speed alarming the survivors into a scattering dash for home.

A woman polishing a red verandah is telling her friend, who has stopped by to chat, about her brother who was stabbed in a shebeen as he drank and danced to a sharp township jive.

On the hot rockery a tiny gecko pops out of a soft-shelled egg.

A baby tied on its mother’s back squalls until she shushes it and rocks it with a little torso sway, rhythmic enough to quiet the baby, smooth enough not to disturb the parcel she carries on her head.

What books can compete with the drama of sudden life and death that plays out in an African childhood?

Swap the sunshine for the quiet gloom of a library, the children’s section wooden shelved and parquet floored. There are some sort of blinds across the windows so that the light is muted and mysterious. It is silent. The occasional whisperwhisper hisses across the spaces. Books are lifted and quietly placed, footfalls are careful.

There is a sense that there is something serious about reading, that however good a time you are having caught up in a book, there is some weighty alchemy at work.

The books – cold weather stories, narratives played out against European or English or American interiors with sorties onto moors, into bleak landscapes, onto rain-soaked streets. Black Beauty. Little Women, Little Lord Fauntleroy. The Secret Garden. Ballet Shoes.

Where is Africa in this written world? Transmuted into the overwritten dramatics of Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, an Africa far removed from anything recognisable to this African child. Jock of the Bushveld causes tears to flow. This is a different Africa too, but more attuned to the stories told in history lessons and so has the surety of echo, even as it fades.

In this story the child can go to the library every Saturday and then revel in an afternoon’s reading spread out across the bed, no chores to disturb this luxury because this is Africa, and the only chore not left to the domestic worker employed in the household by the spoilt, young, white children is the morning making of that bed, the child’s mother believing that some idea of housekeeping should be instilled. There are series to be raced through: Enid Blyton, which results in endless games of “boarding school” in which children pretend the sort of escapade that Blyton’s characters find themselves in; Nancy Drew; The Hardy Boys. Oh, to zip around the world solving mysteries!

The back shelves of the library yield richer books, blessedly almost always available – A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, The Red Badge of Courage, The Scarlet Pimpernel, Robinson Crusoe.

How extraordinary it seemed to me then, and still does, that you can walk out of a library with several books, such richness, the only cost the risk of slipped equilibrium that a good book brings.

There are a few book shelves in that child’s house upon which books stand in a strange gathering – a biography of General Smuts, Renoir, my Father (by his son), Time Life books about countries in Europe, Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country, Sarah Gertrude Millin’s God’s Step Children, Roberts’ Birds of South Africa.

Into my childhood home would come, in January or February, a brown paper parcel adorned with string and sealing wax, a Christmas present sent surface mail by my Uncle John who lived in what was then Rhodesia. The parcels were always books, which I loved. Who knows how he chose them? A man whom I only came to know later and then in disparate snatches, he was at the time single, and childless, and yet he had an unerring knack of sending me the exact book that I would have chosen myself.

Winnie the Pooh came one year. The Wind in the Willows another, Peter Pan, and the very grown up The Art of Margot Fonteyn – a gift by which he paid serious attention to girlish dreaming.

These were precious. I have them still, except for Peter Pan which I took to school and which the teacher read to the class and then, in a sleight of morals astonishing in a nun, declared the book to have been the classroom’s all along. All year I would see it on the shelf. I did not forgive this duplicity.

There was a book that I found by chance in my school library when I was a young teenager, the name of which never stuck, in which there was such a vivid, gripping account of childbirth that I would borrow it frequently, just to read that passage. I thought I was doing it for the information but I realise now that I was captured by the raw power of the description. I was hopelessly in love with words, I just did not know it yet.

School – a trial and a tribulation – well, several, actually, nevertheless gave me Shakespeare and Austen, for which I am immensely grateful, and poets in whose company many a bleak and triumphant hour has since passed. In my last few years at school the redoubtable Lorna Schiemann was my English teacher. What joy to be taught by someone who took literature seriously and expected her pupils to rise to its exacting standards!

It was a joy too to discover, down the road at the Savages’ house, a friend’s parents with whom one could discuss a poem without feeling awkward, talk about the nuance of a line or the musicality of cadence and pause.

In the sorry moral mess that was South African society under Apartheid, a teenager looking for alternatives couldn’t go far wrong with Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. It probably fed my highly romanticised notion of using the law to combat injustice, a naivety dispelled rapidly by the subject matter that formed the backbone of legal studies.

At the University of Natal in Durban, the library was housed on seven floors of a narrowing tower block. The reference library was on the first floor and there I was supposed to sit in between sociology students and anthropologists, amongst history majors and Hebrew scholars, reading about comparative African government and administration or looking up Latin texts. This floor was banked with windows, light and businesslike, and I hated it. The higher one climbed in the tower, the more like a real library it seemed to me, so that on the top floor, a tiny space, probably about three metres square, lined with musty shelves and with a bank of shelves in the centre, it was possible for this willing Rapunzel to read books and be at peace.

Only once did I see another person in this space and it startled me to realise I regarded it as trespass. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight lived there and the good knight’s Loathley Lady. Beowulf, in different editions, sat on a dusty shelf. The books of this floor had cloth or leather bindings. Where there were margin annotations they were nibbed in Indian ink.

In the refectory a strange, older man who always wore black and whom I did not like, told me to read Thomas Mann and acquaint myself with Quasimodo. Such was my search for something other than constitutional law or international law texts that I spent scarce money to buy them, and read them.

I found William Faulkner and Ralph Ellison and Sylvia Plath.

When I first began to work as a journalist I was surprised that few of my colleagues seemed particularly interested in reading books other than thrillers. I don’t know what I had imagined – a kind of writerly, passionate discussion about books, perhaps. But the journalists that surrounded me in my first newsroom were a hard-drinking, hard-playing bunch whose engagement with books was somewhat different to mine.

Once I asked the extravagantly named Justice Alexander, who had an air of authority as well as portly, balding middle age, what an aspidistra was, as in Keep the Aspidistra Flying, because I was trying to write a clever line in a story. He was so insulted that I thought he would have knowledge of a book with such a namby pamby title that he sniffed for a week.

Those early colleagues also seemed reluctant to write anything except the breaking news and the occasional backgrounder or feature. They did not write to their distant mothers or keep fascinating journals. It was as though their daily quota of words somehow wore them out whereas it left me gasping for more.

Later, when I worked for The Star newspaper in Johannesburg I realised that there were jobs within newspapers which would feed this hunger. One of The Star’s assistant editors took responsibility for matters literary and organised reviews of books. No-one so lowly as a reporter would be asked, the books were sent out of the building mostly, or written about by associate editors. But it was hope, nonetheless, and it kept me, for a long while, believing in a literary undercurrent to the daily practice of journalism. A friend gave me Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and this seemed further confirmation that breaking the boundaries between different forms of writing was possible.

In the meantime, books were strictly an out-of-office-hours pleasure.

Black American women slipped in to the chasm waiting to be filled by the writing of black African women, and men. Alice Walker, then still in her literary phase as opposed to her later polemical bent, and Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou and Ntozake Shange came into my life.

In South Africa, J. M. Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer wrote books, the towering talent of which have long endured. Andre Brink, writing on the edge of sedition against the unjust government tried to find fellow travellers of the heart.

Let’s step onto a side path here. Imagine this – a stone house just outside Nairobi, in Kenya, with tall trees framing, in the distance, the Ngong Hills. This is land that once was Karen Blixen’s estate, and in that stone house I sat, reading her book, Out of Africa….

“I had seen a herd of elephant travelling through the dense native forest, where the sunlight is strewn down between the thick creepers in small spots and patches, pacing along as if they had an appointment at the end of the world…”

Like Karen Blixen, I could go a short distance and find the animals of Africa – giraffe, rhinoceros, cheetah, lion, elephant – going about their business in forest or on grassy plains dotted with acacias.

Rose madder sunsets, a fire to combat the night chill which 6000 feet of altitude brings even on the equator, the house empty except for Vivaldi’s fluted notes, fierce dogs, an inscrutable African grey parrot, and the company of writers, living and dead. In the daytime, I did the few hours’ work it took to find African stories and to write them for newspapers that regarded the continent as quaint or savage or the wellspring of stereotypes, stories that an old Africa hand for an illustrious newspaper in London would peruse and then, in those days of carbon paper, say to me, “Give us a black, old boy,” and wander off to file his version of my story so that he could make the Muthaiga Club in time for pre-lunch drinks.

Then I was free to wander the Nairobi streets, make my way past hawkers selling amber, and beaten metal jewellery, past the shop that sold saris made of silk and iridescence, to the bookshop. Like the Karen duka – the little shop where you could buy clotted cream and Twinings tea though there was desolate ground around it and people with torn clothes, pinned together, shopped there – the book shop was a treasure store. I bought the Paris Review Interview series, Writers at Work, in five volumes (I have them still though they are stained and marked, but that is another story and a path too twisted to traverse.) I found John Fowles and read all his books then in print, one after the other.

In the early 1980s I spent two years in Zimbabwe where bombings, the newly independent parliament, the hoarse complaints of suddenly unstructured white people were formed into stories of hope and despair. This was punctuated as always by my reading. Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet riveted me for a week, its meshing of prose and poetry, of form and function, elated me.

I tried it again about 20 years later and was amazed by its self-consciousness, and put it away lest my gratitude for it be damaged by rereading.

In that strange community that forms among journalists from other places who work in Africa, it suddenly dawned on me that I was, finally, among colleagues who read and who read books that I wanted to read. Maybe I had grown older and into company that appreciated the things of the mind as well as the body, perhaps some magnetic force had been working.

I came to Australia in 1985, eight weeks short of my first child’s birth. In Perth I waited for my baby to arrive. I bought the first of Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet to read in hospital. No baby came. I read the book. I bought the second, still no baby, so I read that. Ten days after the due date, with the entire quartet read, I went into labour. I can’t remember the book I took with me to the hospital to read because my friend Bryan Bourke brought me Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia, and I read that instead. I know Chatwin is flaky on some of his facts, I know how flawed the books are, but, with the possible exception of Black Hill, from then on he was a writer with whom I would stop long enough to share a story.

In the fog of tiredness that is motherhood with non-sleeping babies or toddlers or both, I heard Tim Winton being interviewed on the radio about That Eye the Sky. On a hazy afternoon, with a baby sleeping across me, I read Elizabeth Jolley’s Five Acre Virgin, and laughed aloud, and I knew that whatever strange things I encountered in this new land there was a conversation I could enter, a passion I could continue. Everything would be all right.

For the rest of my working life I have been caught up with books – I was books editor at The West Australian and then, later, literary editor at The Canberra Times. I review books, and occasionally edit them.

There is a price to be paid for working amongst books. For much of this time I had to suspend my susceptibility to the siren song of story. (What a lot of alliteration!) If I am reading a book to review it I have to stay on guard, monitor my reaction. Occasionally the book will take over in this process and steal my critical faculties and I have to start again in order to review the book. Sometimes I am reading a book that makes me jot notes – “but why?”… “impossible!”… “lost the plot!”.

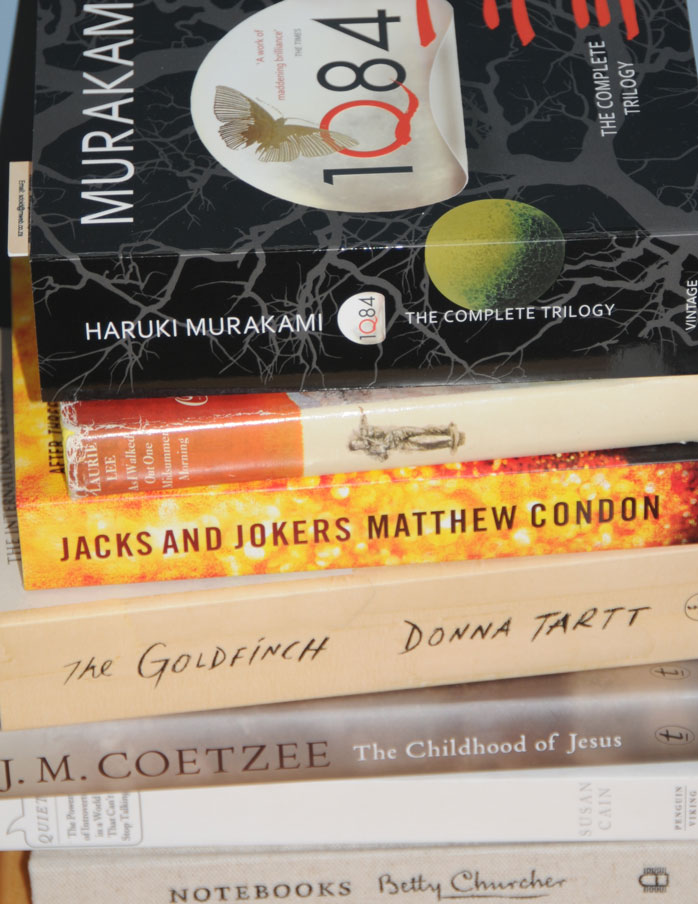

To compensate, in the life of a reviewer, every day is like Christmas. Packages of books arrive, are scanned, sorted into piles to be reviewed or not. I am surrounded by books, books there is not enough time to read, books I want to treasure and to talk about.

In the years since I left my parents home – more years now than I ever lived there – the numbers of books they kept grew with leisured retirement and then declined as my father culled them, getting ready to move into a smaller house. They gave away many, church fetes and second hand stalls have some of what I think of as my inheritance, for nothing in that house would make me wish for it more than the books.

I have a few, rescued by one sister, packed into a picnic basket and flown across the Indian Ocean by another.

“Don’t send any more books,” my Dad admonished me at the time, because he knew that I would soon send a present. “There is no room for them any more.” My father read library books by the score. We are a line of readers on his side. His grandfather, made gleeful by the advent of the Penguin paperback, read one a night.

My mother, on the other hand, doles out her reading more sparingly. I cannot remember her with a book on her lap when I was young – only her needlework or knitting. Exasperated by my mothering of my boys, out of alignment with her own ideas, she muttered at me once: “You read too many books,” as though my common sense had flown out as words flew in. The older she has grown, though, the more I have seen her read, and sometimes we enjoy the same books.

There have been times when I have not read enough, or read little snatches of books without finding the time or the inclination to sit for the full stretch that a book demands. Such scattiness always leaves me slightly crochety, unanchored, as though I have been refused dreams and forced to sleep unrestful sleep.

I need to read like breathing. I need the intake of oxygen that comes when the cover is opened and the delicious scent of prologue or epigram wafts from the page. I need the measured air that fans written passion, beauty and light. I need to exhale the small sighs of pleasure when a writer has picked just the right words, the little gasps of recognition of the carefully written truth, the oh-my-god of finishing the consummate novel in which one would not change a thing, in homage to which one wanders the bookshelves in gratitude, looking for another such book.

© Jennifer Moran