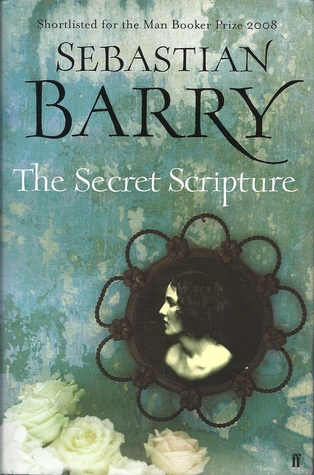

A sacrament in the

search for truth

Some of Sebastian Barry’s characters appear in more than one book and so it is with Roseanne, one of the two first-person narrators in The Secret Scripture. We have previously met her briefly in The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty, where we learned that she had been married to Eneas’s brother Tom and Eneas himself had a somewhat puzzling encounter with her.In The Secret Scripture, Rosanne is an inmate in the Roscommon Regional Mental Hospital. She believes she has no one left outside to remember her. Her people, the “few farthings of them that once were”, are all dead. Dead too her “persecutors”. She is “a thing left over, a remnant woman”. She thinks she may be 100 years old but no one knows for sure. Her decades-long stay at Roscommon was preceded by years in the Sligo Asylum. Roseanne is writing secretly, hiding her pages under a floorboard, to make sense of her life and of the world.

The other narrator is the psychiatrist Dr Grene, who keeps a journal to ground himself in the freefall of emotions surrounding his damaged marriage and his wife’s death. It is his task to assess all the inmates at Roscommon to determine who should move from the crumbling building to the newly constructed facility and who should be allowed to move back into the world.

If you’re trying to make sense of history or story, writing it is useful, as Barry has demonstrated in his previous novels (the afore-mentioned Eneas McNulty, Annie Dunne, the Booker Prize-shortlisted A Long, Long Way) and his plays (Boss Grady’s Boys, The Steward of Christendom, Our Lady of Sligo and The Pride of Parnell Street). Barry teases out character and through character, explores social and political history, particularly the muddled, troubling, violent milieu of 20th century Ireland. Within that, he never lets his readers escape the particular stories of people hemmed in by religion and bigotry, badgered by family, forced to choose sides, constantly questioning loyalty and paying a heavy price for being in that time and that place. People who, nevertheless, are determined in their search for joy, resilient in their quest for love. One might say a terrible beauty is born.

Though his subjects are dark and painful, Barry’s imagery floats like a blessing, his words a vibrant lifeline to redemption through seas of tragedy. Some paragraphs read like poetry. Think Dylan Thomas – the lush cadences and stacked simile.

In The Secret Scripture the confounding nature of memory – its lapses and false echoes, its role in creating narrative – is a primary theme, as is perception, clouded by prejudice and belief.

Roseanne’s recollection of her meetings with Eneas, for example, are quite at odds with the way the omniscient narrator of The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty tells the story, both in the circumstances and in tone. That narrator gave us a knowing Roseanne, a bit mad, a little trashy. The Roseanne that emerges in her own account is altogether more thoughtful, more gracious, more damaged. Her language is educated, philosophical. Her written story grows fluent. Yet she hardly speaks.

In this silence, the Roseanne Dr Grene thinks he has uncovered is someone else again – a young woman labelled a wilful sinner in notes provided for her committal to the Sligo Asylum by the severe priest, Father Gaunt, who delivers punishment as though it were his duty or his due. Though her “sin” would barely be noticed in modern Ireland, though his cursory observations of her over the 30 years he has worked at the hospital have forced a kind of admiration and liking for Roseanne, Dr Grene is a little slow to read between the lines. Forced to consider her more carefully for the move, Dr Grene finds the odd gesture and the slivers of information offered during his visits to Roseanne begin to undermine Father Gaunt’s account.

What is undeniable is the past’s continuing presence. In Roseanne’s recollections of her childhood and early adulthood, political allegiances and the violent struggle for nationhood are tangled with the coarser threads of religious intolerance. As if that were not enough, even amongst families righteous cruelty and meanheartedness complicate things. A life taken with a bullet or a life taken by committal to a mental institution are just two of the ways to rearrange the world.

Roseanne’s fateful meetings with John Lavelle, and with Eneas McNulty, have repercussions in her old age. Dr Grene’s past is waiting for him but not in the form that he expects.

Which version of Roseanne should we trust?

In The Secret Scripture Barry twists his two accounts to an interesting, if risky, knot. Faithful readers will go with it and even sceptics might forgive it, Barry having offered us sacrament as he searches for truth.

© Jennifer Moran