Pens as artefacts of

lives and history

There is something intimate about a pen – its peculiar characteristics endear it to the user; its close association with writer or statesman or history makes it interesting to the rest of us.

As a tool, a pen proves its worth with functionality, its adaptation to the human scale. The best pens take account not just of the necessity of making a mark upon paper but also of the hand that will hold it.

Some pens are beautiful – their form as carefully designed as their function. Some acquire beauty as fingers polish their wood with use, as a nib is ground to make perfect letters.

And some are plain ugly, but fascinating nevertheless. A pen in the National Library of Australia Collection, once owned by Henry Lawson, is a case in point. This is how it looks: A stub of pencil, mustard yellow, has a nib bound to it with a roughly knotted, roughly wound piece of string. The string is discoloured with ink and, possibly, sweat. Underneath the string is another binding, black – perhaps embroidery thread. On the lower end of the pencil the paint is shaved and the initials R.N. and a smudged third letter, which might be another R or a D, are written on the bare wood beneath. The nib, rusted now, has a half-moon cutout.

A note with it reads: “The pen in this envelope was one used by Henry Lawson at Leeton, N.S.W. It was given to Clair Kennedy by Mrs Jim Gordon (‘Erahame’), and passed on to me by Clair, on 11/11/1963. Harry Pearce”

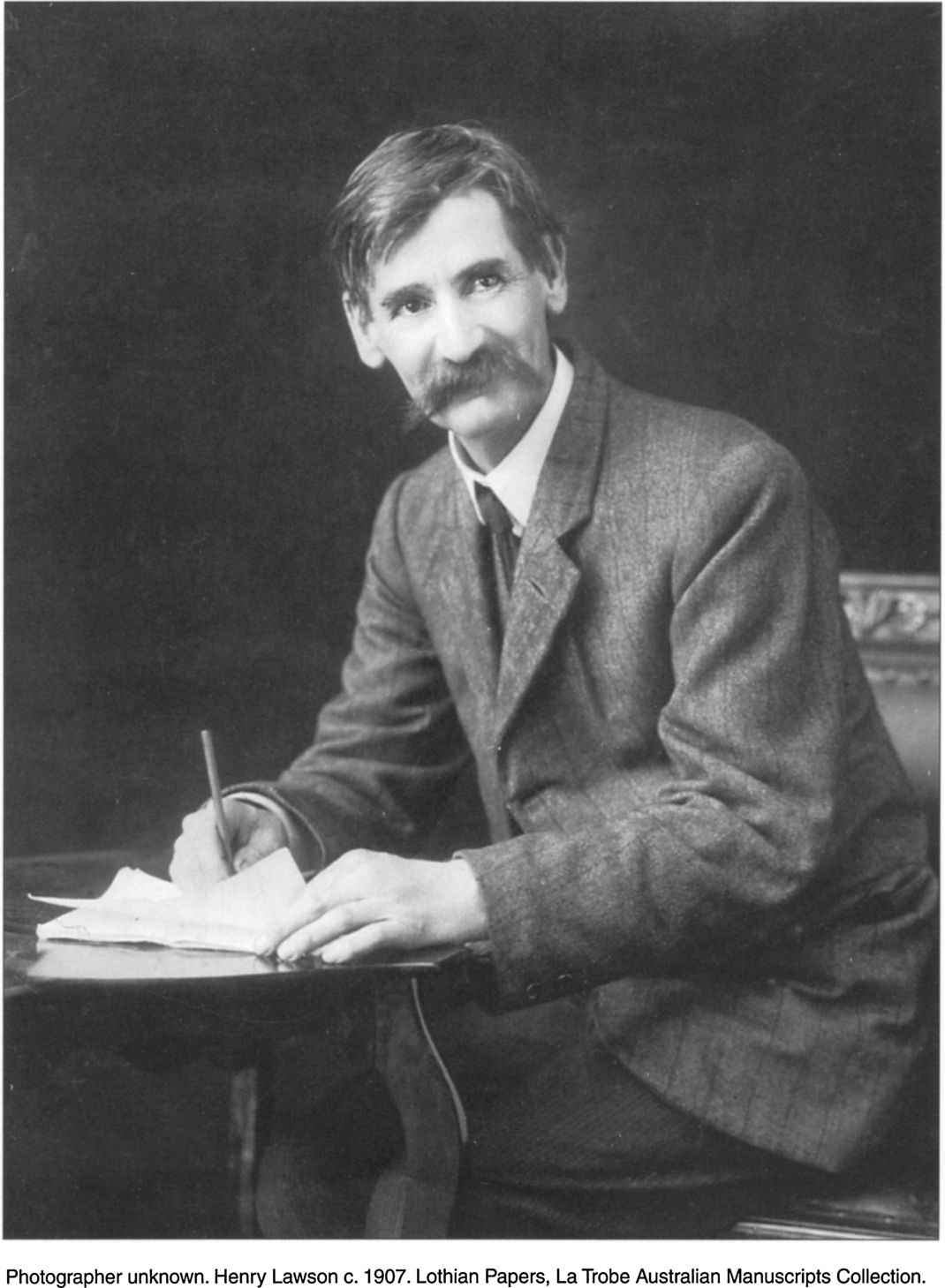

In 1916, Henry Lawson’s friends, concerned about his drinking and his erratic living arrangements, organised a job for him at Leeton, providing data for the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area. He lived at Leeton from January 1916 to August 1917. To look at this pen, fragile now, one must lift it from the box using parsilk (an inert fabric). It is a much more humble instrument than the other pen used by Lawson, kept in the Collection.

The second pen, dated ca1900, is a plain wood pen mounted with a metal nib. The wood is dark, nicely tapered. The end is very worn, the varnish quite gone. Did Lawson suck the end of his pen as he pondered rhyme or structure, or mulled over the words he wrote to his friends? It has an elegant, silver-coloured nib holder, pitted now; the nib itself is classic, spare. The tip is not symmetrical, whether ground for italic writing or simply broken is not clear.

In 1900, Lawson went to England with his wife Bertha and their children. He had been a correspondent of Miles Franklin and, in England, promoted her work as well as trying to make a name for himself as a writer there. But this English sojourn was not happy. Lawson apparently drank excessively, Bertha was hospitalised and there was other misery in the marriage. Lawson did write the four Joe Wilson stories in England and some of his work was published there but, as reported in the Australian Dictionary of Biography (Online Edition), “Lawson himself in later years provided fuel for the idea that his English interlude, so eagerly anticipated, was in fact a catastrophe: ‘Days in London like a nightmare’; ‘That wild run to London/That wrecked and ruined me’.”

The pen came into the collection from Mr John Vincent, from Croyden in New South Wales. A note says it came “via [Dame] Mary Gilmore”, who was Lawson’s friend and defender.

A manila envelope bears the inscription: “A pen of Henry Lawson’s, given me by Mrs Byers, M.G. Given by me to the Henry Lawson Society, Sydney. Mary Gilmore 23.3.44.”

Mrs Byers was, of course, Isabel Byers, Lawson’s protector and sometime saviour, who from 1904 until his death in 1922 frequently provided lodging and succour.

Lawson’s knockabout pen and his earlier implement are a far cry from the pen owned by former Prime Minister W. M. “Billy” Hughes, held in the Library’s Collection with other personal effects dated from 1900 to 1940. The little digger’s golf stick, his false teeth and his hearing aid might be interesting to all sorts of researchers, one imagines, but his pen – instrument of signature and jotted thoughts – is evocative for different reasons, too. Technology was replacing the simple nib pen. Hughes had a Waterman’s Ideal Fountain Pen. It is cradled in a velvet case adorned with Waterman’s proud motto “Makes its mark all around the world” inside the lid. Hughes’s initials are engraved on the pen. It is black, trimmed with gold, and possessed of the then-fashionable pump lever used to fill the reservoir with ink.

As Hughes himself said: “There was a time when the constitution of this country was in my fountain pen.”

The fledging of the national seat of government is marked with another pen in the Collection – the pen and inkwell used at the first sale of leases in the Federal Capital Territory.

The silver lid of the inkstand is engraved: “This Inkwell was used at the first sale of leases in the Federal Capital Territory conducted on behalf of the Government of the Commonwealth by Richardson & Wrench Ltd Sydney and Mssrs Woodgers and Calthorpe Queanbeyan on the 19th December 1924.” The bottom of the inkstand is glass, the base cut in a diamond pattern in rows. A hallmark on the lid and maker’s mark show it to be from Birmingham, sterling silver, and made in 1918.

The pen is long and silver, and tapers to the end, with a small knob to finish it. The underside of the nib is gold.

There is a mallet, a gavel really, in the set, presumably used to knock down each lot as it was sold.

Particular acts of government are sometimes themselves commemorated with a pen. The fountain pen used to sign the security treaty with the United States and New Zealand in 1951 (the ANZUS Treaty), is held in the Collection. On September 1, 1951, the Australian Ambassador to the United States, the Honourable Percy Spender, signed the treaty in San Francisco.

Historical documents released by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade include the “Statement to be made by Spender” at that occasion. The treaty marked, he said, “the first step in the building of the ramparts of freedom in the vast and increasingly important area of the Pacific Ocean…” Labelling the Treaty “an instrument not of offence but of defence”, Spender declared it “a pact for peace”.

“Australia is a nation of peace. It has never sought to interfere – nor will it ever – in the affairs of other nations. But it is equally determined that other nations shall not interfere in its affairs. … it prides (sic) above all other things the great freedoms for which over many years men and women have struggled to achieve and to hold – freedom to worship, freedom to work and live together without fear of aggression from without or tyranny from within, freedom to associate peacefully for social progress, remedying of injustices, and for improving the lot of the underprivileged, freedom to strive for that form of society which will best secure and preserve for them constitutional liberty, social justice and equality before the law, and such is our dedication to these principles that there is no effort we will spare that they may not be imperilled.”

The eleven articles of the treaty set out the parameters of the agreement signed by Spender, C.A. Berendsen for New Zealand and Dean Acheson, John Foster Dulles, Alexander Wiley and John J. Sparkman for the United States.

The commemorative pen is black – a Sheaffer made predominantly of plastic. Towards its narrow end, lines are close-etched into the surface. It is decorated with a gold band on the lid piece and a gold pocket clip. Above the clip is the trademark white dot of Sheaffer pens. On the gold band is engraved, SECURITY TREATY 1951.

The lid unscrews, it has a metal thread inside and a corresponding narrow metal band circles the pen. The nib is rounded, gold, it’s tip silver coloured, perhaps it is iridium. Sheaffer. Made in USA 14k is engraved on it.

Little dots of dried ink fall from the lid or nib as the lid is unscrewed, traces from a brief time when the world hoped that the pen was indeed mightier than the sword.

A Version of this article first appeared in The National Library News. © Jennifer Moran