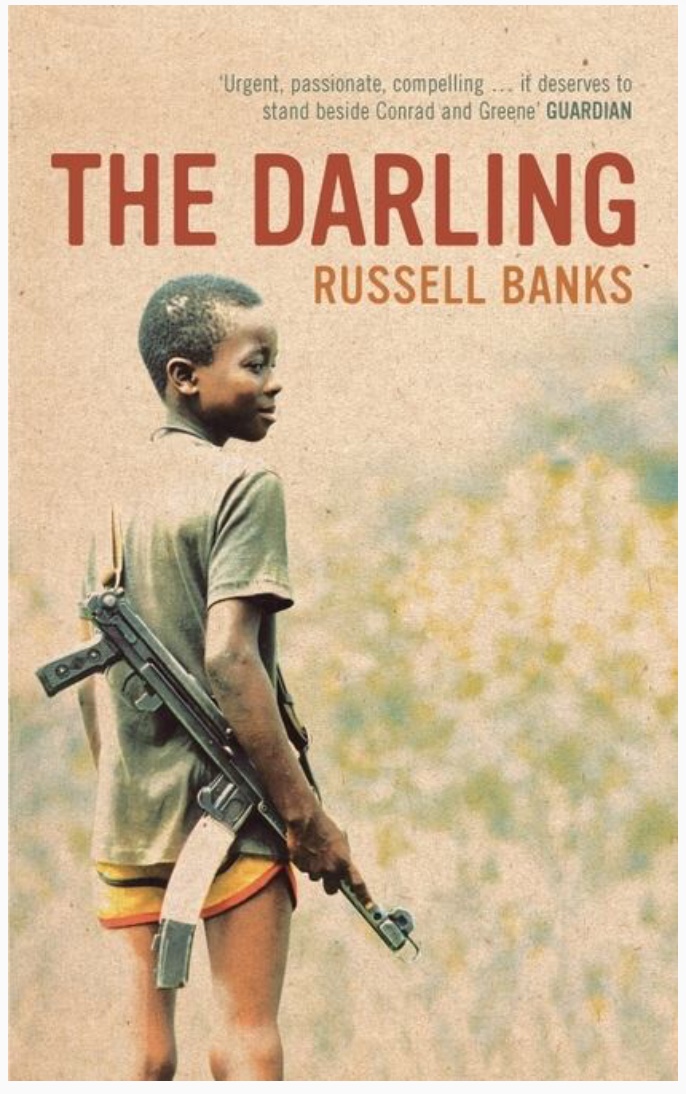

Life subverts subversion theory

Russell Banks leaves no quarter for comfort in The Darling, yet so controlled is his construction that it is not until the end that the reader allows the full awfulness in and mutters, like Joseph Conrad's Kurtz: "The horror, the horror."It might be that in reading the first-person narration, we know that Hannah Musgrave survives and we assume, therefore, that all is not lost. It might be that in her detached telling, her sense of separateness (upon which she remarks), we are kept at a level at which we can bear to go on reading. Banks weaves this fiction with historical fact and his characters mingle with real people. Various presidents of Liberia make appearances, including Charles Taylor, who went into exile and later was found guilty in The Hague of crimes inclding terror, murder and rape.

Banks doesn't just borrow from history; The Darling has a literary antecedant. The novel's title is the same as that of a short story by Anton Chekov in which a woman takes on the opinions of her serial lovers - a theatre manager, a timber merchant, a veterinarian. After two of these die and a third marches off with his regiment, her opinions dry up and she becomes a husk of a woman until the vet returns to the area with his formerly estranged wife and their son. The former lover then focuses all her attention on the son, identifying utterly with him.

Banks writes something more elaborate and truly tragic. His "darling" is Hannah, an American and ostensibly a woman quite able to express her own opinions - although these might be explained as successive manifestations of rebellion against her parents, the adoption of feminist and socialist theories of the late 1960s, the mores of black Africa and an emerging eco-tourism boom. And when, finally, it seems to her that there is some way that her early beliefs can marry with her disjointed life, there is also the danger that she might simply be acting in the broader imperial interests of her birth-country.

In telling her story, Hannah meanders back and forth from the farm in the Adirondacks, where she has found refuge in her 50s, to Liberia, where she lived her middle years, and to her privileged childhood as the daughter of a celebrity paediatrician (think Dr Spock) and a compliant, self-absorbed mother.

In her youth she drops out of Harvard to join the Weather Underground, becoming adept at passport forgery and bomb making. Wanted for these activities, she escapes to Liberia, where her aborted medical studies get her a job in a sham laboratory, an appalling place where chimpanzees are kept so that US pharmaceutical companies can test the consequences of disease and drugs on primates. She marries a government official, Woodrow Sundiata, and finds herself living the kind of stunted life she despised her mother for - reliant on Sundiata, accepting humiliation, channelling herself into the only connection she can make to give her life meaning: looking after chimpanzees. Life throws Hannah's early aspirations back at her in a distorted form. She finds herself caught up in the real thing, her socialist subversion training in the Weather Underground no preparation for a war in which heartless thugs decapitate her husband and in which her sons - sweet,polite boys - grow into killers who call themselves Worse-than-Death, Fly and Demonology. Banks's ending comes with a kind of left-field moralism that is further evidence of why this author, probably best known for Cloudsplitter, The Sweet Hereafter and Affliction, deserves to be read. © Jennifer Moran. A form of this review appeared in The Weekend Australian.