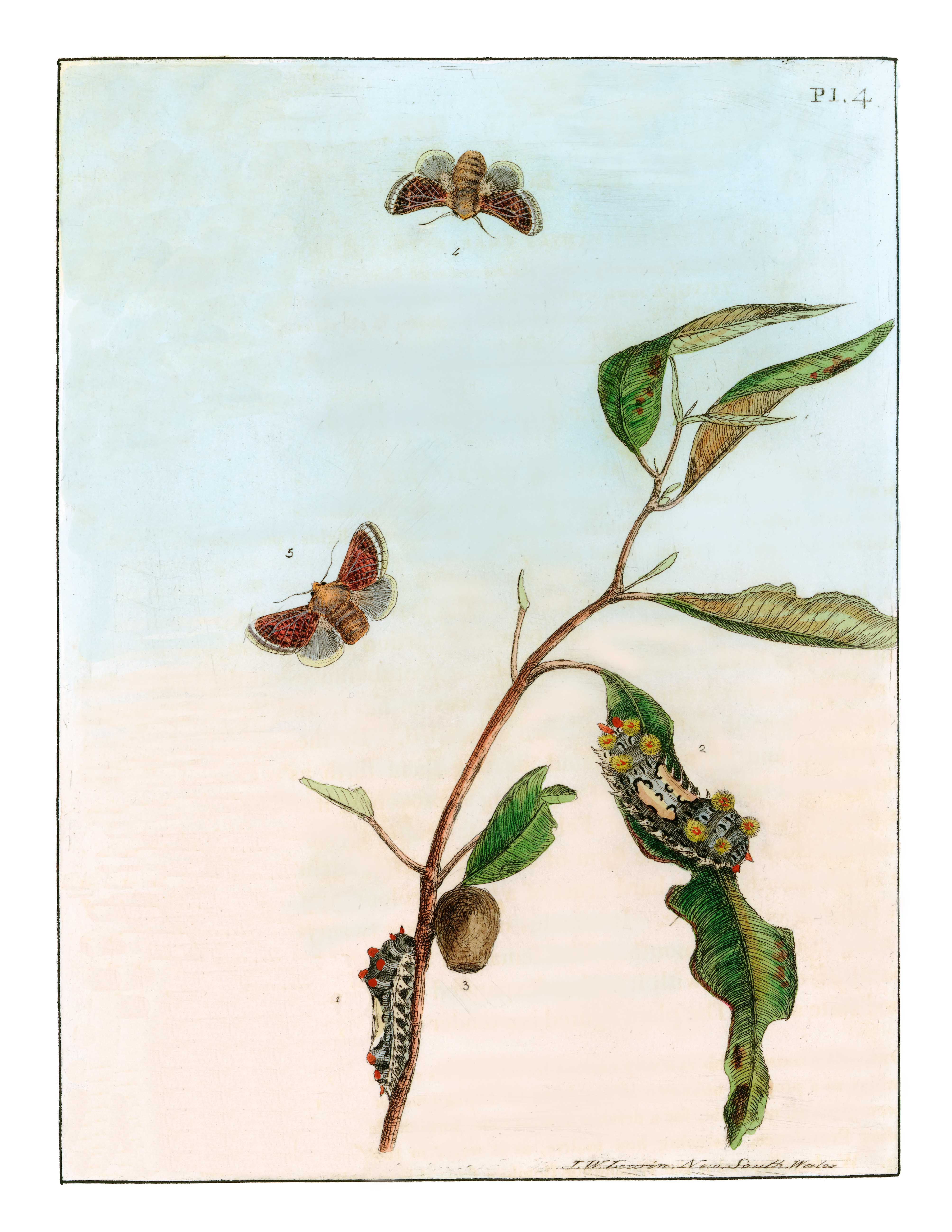

Lewin's lepidoptera

Hunting moths might seem tame to anyone who hasn’t done the long hours of careful searching with torch or lamp, beset by other night insects and strange rustling in the grass. But the backbreaking work of crouching under likely bushes counting larvae or the quick capture of a moth for observation without damaging its fluttering wings is not for the fainthearted. It requires patience, persistence, a keen eye and a passion for the less-flashy lepidoptera.

Finding moths in the fledgling colony of New South Wales in the early 19th Century must have been even more difficult with its logistical and material challenges but, compared to the other trials of the young John William Lewin, it probably seemed a picnic.

Lewin, credited by some as being the first artist to truly paint with the palette of Australia, and whose books on moths and birds were firsts for Australian publishing, was a young Englishman with good connections and a passion for travel. He had served a valuable apprenticeship in painting, drawing and engraving when working with his father, the natural history artist William Lewin who had, with the help of John and his brother Thomas, produced The Birds of Great Britain, London, 1789-94.

Keen to go to New South Wales, Lewin sought help from his patrons – the Duke of Portland, who interceded on his behalf, requesting that he be supplied with rations in New South Wales, and the natural history collector, botanist and mycologist Lady Arden. The entomologist Dru Drury supplied him with equipment, materials and money, in return for which Lewin promised to send specimens.

But the much-anticipated journey went from auspicious to disastrous on a favourable tide. The artist, in his late 20s, was booked to sail on the Buffalo in 1799. His wife Maria, also a talented artist, was already on board.

For some reason not known to us, Lewin missed the boat. Whether the Buffalo left unexpectedly or whether he had misjudged its departure is not clear. Nevertheless, it was not until eight months later that he was able to join his wife. A passage was found for him on the fast transport Minerva which was due to take convicts from Ireland, but when Lewin joined the ship there, the Irish rebellion delayed the departure for several months and Lewin did not arrive in Port Jackson until January 1800. As if that were not a difficult enough situation for Maria and her tardy husband, by the time Lewin arrived in the Colony, Maria was embroiled in a lawsuit. She was suing George Thompson for £500 damages for slander.

On the ship Maria had been taken under the wing of Captain Raven and his wife and had been living with them in New South Wales. The court heard that rumours had circulated in the community which cast aspersions on her character. These had been ignored. Then, when Captain and Mrs Raven were out one day, the first mate of the Buffalo, Hugh Mackin had come to the door. Maria claimed that after she spoke to him, he left but that the Ravens’ servant Thompson had accused her of improper behaviour. Deeply upset, she had gone to her friends, The Reverend Richard Johnson and his wife, and Johnson had advised her to clear her name by bringing a case against Thompson.

When Lewin arrived in the colony, the case had been providing gossip for the community for some months. Lewin entered the case as a joint plaintiff and the court found in the Lewins’ favour, awarding them £30 and costs.

The court case delayed Lewin’s work but soon after he began collecting specimens and recording various stages of the growth of lepidoptera. Nevertheless, making a living from his art in the colony proved difficult. In 1801 he set off as artist on the Bee, the tender to the Lady Nelson, on an expedition to Victoria but the Bee had to turn back because it was not seaworthy. Three months later Lewin did have a successful journey on the Lady Nelson to Port Hunter and the Hunter River but, in November that year, his run of bad luck continued. He sailed on the brig Norfolk which was sent to Tahiti for supplies. By the time the ship arrived in Tahiti, a civil war had broken out and the ship and her crew had to spend nine months on the island.

On his return to New South Wales he began to fulfil his obligation to Dru Drury, settling down at last to his lepidoptera study. Within three months he had 20 drawings with larva, chrysalis and moth ready for engraving.

“All the species illustrated were reared from larvae and in all cases this biological information was quite new,” said Mr Ted Edwards, a Post Retirement Fellow at CSIRO Entomology. “The foodplants of the larvae were illustrated and the habits of the larvae, if leaf feeders or borers, was indicated. Lewin found some very cryptic moths and his work set a standard which was emulated by A. Walker Scott (and his daughters, Helena and Harriet) in the book Australian Lepidoptera and their Transformations, Volume 1 of which was published in 1864. Lewin had immense influence on Scott’s work although he was dead before Scott came to Australia. His book must have been a bible to Scott, and in turn they influenced many later lepidopterists.”

In their study of Lewin in Early Artists of Australia, (Angus and Robertson, 1963) Rex and Thea Rienits quote Lewin’s letter to Dru Drury, written on March 7, 1803: “I intend to print 50 Coppeys of the Insects and send them home & while they are [on] the passage to you I shall go about the Birds which you would have had long before this as I had engraved a number of the plates.”

Lewin’s book, Prodromus Entomology: Natural History of Lepidopterous Insects of New South Wales, was published by his brother Thomas in London in 1805. A copy of this edition is held by the National Library of Australia. It contains 18 plates and was dedicated to Lady Arden in “grateful remembrance of that goodness which gave the Author an opportunity of employing his talents, as it were, in a new world…”

It was the first book about Australia that used plates engraved here.

Thomas Lewin’s preface says that Lewin collected, painted and engraved the lepidoptera, “to furnish him with the means of returning to England, his native country, after an absence of near eight years, which he has spent almost solely in the pursuit of natural history, principally in the branches, Ornithology and Entomology; in which he has in New South Wales, and in Otaheite, made some hundred of original paintings…”. (This was a slight exaggeration since Lewin had been gone for only five to six years.)

“Lewin, or his brother in England, had Alexander Macleay do the identifications and draw up the descriptions,” said Mr Edwards. “Macleay knew what he was doing so all the moths were correctly placed in the group (the modern day Family) to which they belong. And in giving them Linnaean names he ensured the lasting scientific value of the book.”

Thomas Lewin also credits the President of the Linnaean Society, Dr Edward Smith and Macleay who was, at the time, secretary of the Society, with helping with the names of plants from which some of the names given the moths were taken.

Mr Julien Renard notes in the Edition Renard facsimile, Prodromus Entomology, or a natural hisrtory of the lepidopterous insects of New South Wales, published in 2007 (also in the National Library Collection), that the prototype book held by the Mitchell Library in Sydney contains Lewin’s manuscript notes and descriptions together with pencilled scientific names of the insects by Macleay and of the plants by Dr Smith.

Macleay would, 20 years later, emigrate to New South Wales to become Colonial Secretary in Sydney. Lewin was never to return to England. He had been given land at Parramatta but after the Rum Rebellion he and Maria moved into Sydney where Maria opened a shop and inn in both the houses in which they lived before moving to George Street. Lewin advertised his services as an artist to paint portraits, landscapes and “works of nature”.

In 1813 his Birds of New South Wales, which had been published in England in 1808, became was the first illustrated book and first non-government publication to be published in New South Wales when Lewin organised an edition for the subscribers of his 1808 edition which had, mysteriously, never arrived in the colony.

When Lachlan Macquarie was appointed Governor of the colony in 1910, the Lewins’ fortunes took a turn for the better. Macquarie made Lewin coroner, an odd appointment (perhaps Macquarie admired his eye for detail), but one which gave Lewin a salary and supplies.

When Lewin died in 1819, aged 49, Maria returned to England with their son, William Arden. She was instrumental in publishing the second edition of his Prodromus Entomology in 1922, this time with the simpler title A natural history of the lepidopterous insects of New South Wales and with an extra, unlabelled plate as frontispiece.

His tombstone in La Perouse cemetery, note the Rienits, is indicative of the affection and admiration in which he was held. On it, Lewin is praised as “an honest man” and “an eminent artist in his line of Natural History Painting, in which he excelled”.

A version of this article first appeared in The National Library News. © Jennifer Moran